PROVOCATIONS

Provocations is a regular feature introducing notable research voices, teams or organisations from critical thinking, creative practice or industry backgrounds.

Kirsten Scott

WHEN ENOUGH IS ENOUGH

First published in Enhancing the Future, 2020

“The moment we are going through is turbulent, but it offers us the unique opportunity to fix what is wrong, to remove the superfluous, to find a more human dimension (...) This is perhaps the most important lesson of this crisis.” (Armani, 2020: on line)

Long before Covid-19, it was clear that the fashion industry had to change significantly to become sustainable: we know that we have only a decade left to prevent irreversible climate damage (UN, 2019: on line). Our soil, our waters and even our food chain have become contaminated with fashion waste and yet consumer culture proliferates (Brooks et al, 2017: on line; Burgess, 2019). Human rights abuses abound within the fashion industry, including modern day slavery, child labour, poor wages and unsafe working conditions - such as those that led to the death of 1,134 garment workers and the injury of thousands more, in the Rana Plaza collapse of 2013 (Niebank, 2018: on line; Niinimäki et al, 2020: on line). The fashion system is broken, in urgent need of rebuilding. The pandemic has provided space to step back and to reflect, to ask questions about the meaning, value and impact of fashion in a post-Covid world.

The Earth’s resources are finite, and yet the myth of green growth pervades: we can continue to have it all, including sustainability! The term ‘sustainable’ means the ability to keep doing something at a certain level, which is at odds with a highly extractive and polluting fashion industry. ‘Sustainability’ has become just a buzzword: appropriated and systematically devalued by numerous fashion brands as they attempt to greenwash their activities. Indeed, some brands spend more money on telling us how sustainable they are than on actually becoming sustainable (Fletcher and Tham, 2020: on line). But what does sustainability in fashion really mean? And what is it that we want to sustain?

The fashion industry has continued to fiddle while the planet burns and has failed to address the fundamental issues of over-production and over-consumption, placing faith in the myth that technology alone provides a silver bullet solution to the challenges faced, so that it can continue to pursue growth (Brooks et al, 2017: on line; Indvik, 2020: on line). New materials, technologies and business models have emerged that begin to contribute to a more sustainable industry. Circular systems for fashion are part of the solution to keeping materials in use for longer and thus reducing waste, but they have so far - for the most part - been led by a desire to carry on with business as usual. Although the circular economy attempts to mirror nature’s own systems, at least 60% of the textiles used in fashion are derived from fossil fuel-based synthetic fibres (Biomimicry Institute, 2020: on line). Even when recycled, the toxic cocktail of ingredients that these contain is not designed to be kept close to the skin and is shed in microfibres during the washing cycle. Claims that these fibres are infinitely recyclable are misleading: most synthetic polymers will last for only 10 cycles and there is urgent need to move towards 100% biodegradable fibres, to design for decomposition (Biomimicry Institute, 2020: on line). A reduction of 75-95% of material resource use is needed, but this is self-evidently impossible in an industry that was forecast to grow 81% by 2030, at least prior to Covid-19 (Fletcher and Tham, 2020: on line; Global Fashion Agenda, 2019: on line). To achieve really significant change, we must flip the question: instead of “how can we make fashion more sustainable”, we must ask “how can fashion be responsible”?

In this context, it was particularly refreshing to hear Margherita Missoni, in a virtual interview with Sara Sozzani Maino in July 2020, within the cycle “Enhancing the Future” (Istituto Marangoni, 2020: on line), talk about how her grandfather, Ottavio Missoni, would cut large orders from his retailers in half. His rationale was simple: if they were to produce the whole order, then they would have to enlarge the business and that would be “a headache”, and they already earned as much as the whole family needed. This almost throwaway statement shows that Missoni had a very responsible and progressive approach to fashion business, in comparison with today’s practices, and one that we need urgently to cultivate. It indicates a strong sense of personal priorities, of work-life balance and of knowing when enough is enough. How many brands would be prepared to do this today? Why is growth considered the benchmark of success in our industry? When is enough, enough?

As Alessandro Michele, creative director of Gucci, wrote on Instagram “So much outrageous greed made us lose the harmony and the care, the connection and the belonging”. (Michele, 2020: on line)

And yet, the show goes on.

Technology and advanced analytics can support more sustainable, demand-driven models that pull products into the market, based on customer demand, rather than pushing them into a flooded marketplace (McKinsey, 2019: on line). The use of automated production or small, agile factories enable a fast response to data-driven orders, but is this enough to ensure sustainability? While so many new business models, new production strategies, new materials and new technologies continue to enter the fashion industry, none of these are sufficient without deceleration and degrowth. Degrowth requires an uncomfortable change of mindset amongst all stakeholders, but there is increasing recognition that we need to produce less, to produce slower and to produce better clothing that will last, that is untied from seasonal trend and more reflective of personal style (Edelkoort, 2020: on line; Armani, 2020: on line). This is a big ask for an industry that has worshipped at the altar of growth for so long; legislation, regulation and green taxation will be needed to ensure compliance and to make brands responsible for their impact. The term ‘sustainable’ may therefore better be replaced by ‘responsible’ – responsible fashion that includes accountability. As Eileen Fisher said “Going forward we need to find a way for all new businesses to have to be responsible for their environmental and social impacts” (Fisher, 2020: on line)

Radical transparency has become crucial to knowing the origins of what we grow, make, buy and wear more than ever before, to ensure best practice throughout the supply chain (Edelkoort, 2020: on line; Burgess, 2019). Technologies have emerged with the powerful potential to support transparency and sustainability, such as blockchain and AI. These technologies may be key to a more responsible fashion industry, particularly where supply chains are global, but by themselves are unable to bring about the fundamental disruption that is needed and are in danger of being used as tech-washing (CompTIA, 2020: on line). Science is needed to complement other transparency measures, for example Oritain works with Kering brands to provide independent, 3rd party, forensic verification of fibre content – even able to distinguish the farm of origin. Their random testing identifies illicit substitutions, adulteration and blending to provide an additional level of veracity to the information entered in blockchain. However, while transparency must be central to any future fashion industry, it cannot be considered an end goal: even the Fashion Revolution Transparency Index (Fashion Revolution Cic, 2020: on line) placed H&M in first place, suggesting that more than transparency is needed to ensure sustainability.

Covid-19 highlighted the benefits of shorter supply chains, showing that local production and nearshoring will be important to fashion’s future. As well as reducing carbon footprint, local sourcing and production support transparency and contribute to more diverse expressions of fashion. At a more extreme end of this movement is Fibershed, a model where local designers work closely with farmers, spinners, natural dyers, weavers/knitters and garment makers to produce clothing within a relatively small area (Burgess, 2019). This collaborative, holistic and relational approach to fibre, textile and garment production is both very ancient and very modern – and can be more widely translatable to contemporary fashion (Edelkoort, 2020: on line). Through using regenerative agricultural methods, it replenishes soil health, actually helping to revive the soil while developing clothing in a way that supports farmers and natural systems. An early adopter of this approach is Eileen Fisher, who is also an advocate for reduced consumption and production; Fisher’s clear Horizon 2030 plan aims not just to do less harm to the planet, but to leave places better than they find them and put measures in place that support the wellbeing of workers in the supply chain and their communities (Fisher, 2020b: on line). Local environmental, social and economic impact is more easily monitored and measured so, by moving towards decentralised and regional production, fashion can support sustainability more effectively (Biomimicry Institute, 2020: on line). In addition, the story telling about how fashion is made and who makes it – from soil to skin – is a potent communication of the values of a brand to consumers who are place increasing importance on these.

Smaller brands may have the autonomy to make decisions about their operations that larger brands don’t (Kibbe, 2015: on line; McRobbie et al, 2016: on line; Moulton et al, 2019: on line). A study for CREATe looked at micro-enterprises in the creative industries in Berlin, London and Milan: these small, diverse businesses were able to define themselves on their own terms and to operate sustainably. Many of the brands interviewed in the study expressed unhappiness with how the fashion industry works and were looking for new ways of doing things at a slower pace that challenged the status quo. Some incorporated aspects of social entrepreneurship in their business models to bring about positive social change (McRobbie et al, 2016: on line). There is a growing force of these small, independent, pro-actively positive brands around the world that are doing fashion very differently, offering diversity, authenticity, and that aim to work within planetary boundaries (Kibbe, 2015: on line). A McKinsey report (2019: on line) discusses this promising phenomenon enthusiastically, but frames it as a starting point for growth – completely missing the imperative need for brands – as well as consumers – to know when enough is enough, in the way that Ottavio Missoni did.

There are signs of hope, as some leading brands – including Armani, Gucci and Vetements - reduce the number of collections produced annually, reduce their size, and begin a move towards seasonless offer. Indeed, Giorgio Armani spoke eloquently about the need for change in an open letter to WWD in April, 2020, where he described the acceleration of production cycles, increased volumes and frenetic fashion seasons as ‘criminal’ (Armani, 2020: on line). His letter is indicative of a growing consensus amongst designers that time is up for the fashion system as we know it, but it will be a new generation of young designers that offer alternative solutions for a better future.

Fashion education has an essential role to play in contributing to a more responsible fashion system, by making sure that students are well-informed about the social, environmental and economic issues relating to the industry, about new approaches and technologies that emerge, and are able to respond to these critically and creatively through their practice to devise solutions. There is a tension between imparting the professional competencies and knowledge needed to be industry-ready and the more critical, innovative, problem-solving skills needed to amend that industry’s trajectory. Students in fashion schools all over the world increasingly are taking an activist position through their work, using fashion as a platform to campaign for environmental, social, cultural, political and industry change. These are the industry professionals of the future and they will be the change they want to see.

A new generation of Istituto Marangoni London fashion design and fashion business students is emerging that are highly attuned to the issues outlined above, who are not wanting to be complicit in what they recognise as a problematic industry, but rather to foster positive change through new, personal and responsible approaches to fashion. Increasingly, these students are focused on setting up their own small fashion brands and social enterprises, where they can ensure that their values are reflected in every aspect of their business model, from fibre through to end product, communication strategies, sales and after-sale. They ask questions about why we keep some clothes forever and discard others - what are the factors that contribute to this attachment? How can they design clothes that people will want to keep wearing forever? How can fashion improve our sense of wellbeing and alleviate anxiety? What additional, beneficial factors can they add to the value chain?

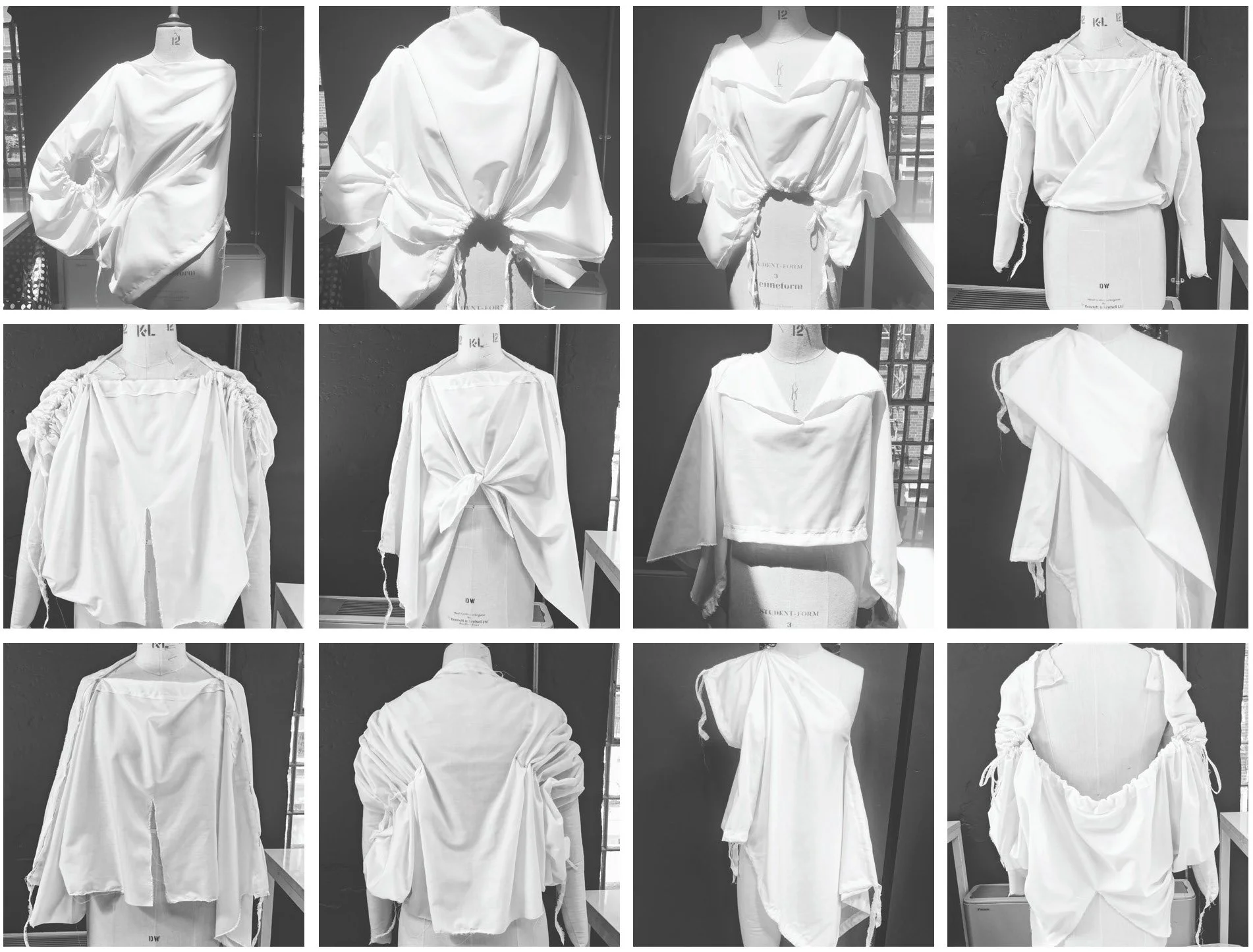

An MA Fashion Design graduate, Karina Ayu Ghimas, focused on how to design for aesthetic, practical and emotional durability, developing a fashion collection as part of her postgraduate dissertation project that has become the foundation of her own small brand: KarinaAyu. These garments are made from natural, organic materials and are endlessly adaptable on the body to create multiple looks. Karina’s tenacious research and 3D experimentation enabled zero-waste techniques to be used effectively to create highly desirable, professional garments that were adaptable by their wearers.

Another graduate, Tamar Kikoria, used identity crisis as a lens through which to explore the perceived oppositions of slow fashion and hi-technology, using organic materials such as linen, hemp and silk combined with laser cutting and 3D printing processes in her dissertation collection. Some garments included detachable elements, such as sleeves, collars and yokes, to make them versatile, making it easy to launder separate elements and ultimately more sustainable.

Increasingly, students are preoccupied with improving the lives of wearers through fashion, using colour theory, art therapy and bold pattern to lift and enhance mood, to create a sense of wellbeing and balance in the wearer, or a focus on texture, surface and silhouette to improve calm. Many have a keen interest in natural dyes and traditional craft, which they seek to both modernise and preserve for future generations. These graduates’ approaches to fashion show their ability to challenge the incumbency thinking that perpetuates current systems with small, quietly disruptive approaches to fashion design and production that re-orientate us towards a more responsible future for fashion that understands when enough is enough.

Reference List

Armani, G. (2020) Open letter to WWD [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020] https://wwd.com/fashion-news/designer-luxury/giorgio-armani-writes-open-letter-wwd-1203553687/

Biomimicry Institute (2020) The Nature of Fashion: moving towards a regenerative system. Biomimicry Institute, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], tps://biomimicry.org/thenatureoffashion/

Brooks, A., Fletcher, K., Francis, R.A., Rigby, D. and Roberts, T. (2017) Fashion, Sustainability and the Anthropocene, in Utopian Studies, Vol 28:3, 2017, pp 482-504, [online], [Accessed on 6 August 2020], https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323430259_Fashion_Sustainability_and_the_Anthropocene

Burgess, R. (2019) Fibershed. London: Earthscan

ComPTIA. (2019) IT Industry Outlook 2020, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.comptia.org/content/research/it-industry-trends-analysis

Edelkoort, L. (2020) Live interview with Bloom Brasil [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.instagram.com/p/B_us9rMn0uQ/

Fashion Revolution CIC. (2020) The Fashion Revolution Transparency Index 2020, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.fashionrevolution.org/about/transparency/

Fisher, E. (2020) Interview by Yotka, S. The Biggest Thing We Can Do is Reduce - Eileen Fisher Shares a Vision for a Sustainable Future, Vogue, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.vogue.com/article/eileen-fisher-amy-hall-sustainabiity-horizon-2030

Fisher, E. (2020b) Horizon 2030: What if we did things differently? [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.eileenfisher.com/horizon2030?country=US¤cy=USD&utm_source=Skimlinks.com&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_content=1&utm_campaign=acquisition_s_m4&ranMID=42820&ranEAID=TnL5HPStwNw&ranSiteID=TnL5HPStwNw-JfJdzGUyu5Zy.uYRGsGrAw#

Fletcher, K. and Tham, M. (2020) Earth Logic, [online], [Accessed on 7 August 2020], https://earthlogic.info

Global Fashion Agenda (2019) The Pulse of the Fashion Industry 2019, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://globalfashionagenda.com/pulse-of-fashion-industry-2019-update-released/#

Indvik, L. (2020) Life After Lockdown – The Future of Fashion, The Financial Times, [online], [Accessed on 6 August 2020], https://www.ft.com/content/1b03efec-8895-11ea-a01c-a28a3e3fbd33

Isabelle, D., Horak, K., McKinnon, S. and Palumbo, C. (2020) Is Porter's Five Forces Framework Still Relevant? A study of the capital/labour intensity continuum via mining and IT industries , in Technology Innovation Management Review, Vol 10:6, [online], [Accessed on 23 August 2020] https://www.timreview.ca/article/1366

Istituto Marangoni (2020) Enhancing the Future: Virtual Conversation with Margherita Missoni, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MHAspwZBGDM&feature=youtu.be

Istituto Marangoni (2020b) Enhancing the Future: Virtual Conversation with Formafantasma, [online], [Accessed on 25 August 2020], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qc08yG1vBD0&feature=youtu.be

Kibbe, R. (2015) Support Smaller Fashion Brands, The Business of Fashion, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.businessoffashion.com/community/voices/discussions/can-fashion-industry-become-sustainable/op-ed-support-smaller-fashion-brands

McKinsey (2019) The State of Fashion 2019, McKinsey, [online], [Accessed on 4 August 2020], https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-state-of-fashion-2019-a-year-of-awakening

McRobbie, A., Strutt, D., Bandinelli, C. and Springer, B. (2016) Fashion micro-enterprises in London, Berlin, Milan, CREATe Working Paper 2016/13, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], http:// DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.162668

Michele, A., (2020) Notes from the Silence, Instagram [online], [Accessed on 9 August 2020], https://www.instagram.com/p/CAfsNzTiLjL/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Moulton, J., Hudosn, S. and Kim, D. (2019) The Explosion of Small, McKinsey, 2019, The State of Fashion 2019, McKinsey, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-state-of-fashion-2019-a-year-of-awakening

Niebank, J-C. (2018) Bringing Human Rights into Fashion. Berlin: German Institute for Human Rights, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.institut-fuer-menschenrechte.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Publikationen/ANALYSE/Analysis_Bringing_Human_Rights_into_Fashion.pdf

Niinimäki, K., Peters, G., Dahlbo, H. et al. (2020) The environmental price of fast fashion, Nature Reviews: Earth and Environment 1, 189–200, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9

United Nations (2019) 11 Years Left to Prevent Irreversible Damage from Climate Change, Speakers Warn during General Assembly High-Level Meeting, 73rd Session, [online], [Accessed on 5 August 2020], https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/ga12131.doc.htm

Image ©2016 MJA Nashir

Sandra Niessen

Writing To Right Fashion’s Wrong.

Sandra Niessen (PhD Leiden University, Netherlands, 1985) is a leading scholar of the clothing and textile traditions of the Batak people of North Sumatra, Indonesia about whom she has written four books and numerous articles and produced a film. She taught for 15 years at the University of Alberta and has worked in numerous museums around the world conducting research, developing exhibitions and documenting collections. A founding member of the ‘Research Collective for Decoloniality and Fashion’ and ‘Fashion Act Now’ she is currently an activist working towards dismantling the Fashion industry.

In November 2020, State of Fashion (The Netherlands) produced an on-line programme entitled, ‘This is an Intervention’. Anthropologist Sandra Niessen was invited to share her thoughts about fashion and decoloniality in an on-line ‘Whataboutery’ and a published ‘Long Read’. She stressed the importance of diversity in dress systems, pointing out that the dominance of Western fashion has had a negative effect on indigenous cultures and their dress systems around the world. Afterwards, she received questions querying her right to presume what others should wear and pointing out that all should have the freedom to choose. This short piece is Sandra’s response to those questions.

Thank you for these questions. They broach the issues of self-determination and self-representation, which were central to the Whataboutery.

What I hoped to do with the Long Read [Niessen 2020b) was to expose the obscured relationship between the system of industrial fashion and the clothing systems of people who have been positioned as being ‘without fashion’. The considerable ramifications of this conceptual distinction have bolstered the sense of superiority of those ‘with fashion’ and intervened in an overwhelming way with the cultures and clothing systems of those ‘without’. Furthermore, the distinction has restricted the latitude of self-determination and self-representation on both sides of the dichotomy. By drawing attention to the impacts of the colonial definition of fashion I have tried to facilitate awareness, and thereby ambition, to foster greater latitude for fairness between North and South in the medium of dress. For me, the ultimate goal is to eliminate fashion’s sacrifice zones – which include indigenous culture systems, also dress -- a challenging goal. I hoped that the Whataboutery would be a step in that process.

It is worth reflecting on why ‘we’ in the North, and especially fashion scholars, have for so long been blind to the ramifications of our ethnocentric definition of fashion. This has extended to not even questioning or testing the validity of this category called ‘fashion’. We have assumed its existence a priori. This realization drives home how subtle, deep and pernicious Eurocentrism and white supremacy can be, and how it can be inherited unseen and unquestioned. Not only has the category of fashion gone largely unquestioned (collectively, historically, from one generation to the next, and even within the hallowed halls of academe) but we have assumed, accepted, expected, and insisted upon its position of superiority above all other systems of clothing in the world. As makers and consumers of industrial fashion, we have become blind to fashion’s complicity in the decline and destruction of the clothing systems (and cultural values) of other peoples. Their position, as falling outside the fashion realm and being thereby conceptually erased, was simply determined by those within the fashion realm. This constituted a profound removal of agency and avenues of self-determination, not just on the side of non-fashion but, seemingly ironically, also on the fashion side.

I consistently point to the value of indigenous systems of dress (full of meaning, historically grounded, sustainable, local) and criticize the global fashion system for undermining those systems. Indeed, I champion their retention. And this is when listeners challenge me on whether it isn’t “up to the communities themselves to decide if they want to ‘buy in’ to the Western system”, given that culture is a living, changing thing that cannot be “preserved in a jar or a museum”. “Everybody should have the freedom to choose,” they point out. The colonial era is behind us; have we learned nothing? And of course I agree.

But there is another way of looking at the matter. Given how hard it has been to scrape the scales from our own eyes (the ‘we’ being the ones positioned as ‘having fashion’), it should be possible to perceive how the lives of ‘other’ people might similarly be guided by inherited frames of thought. I have learned that the inflated ego on the fashion-side of the dichotomy has its complement on the non-fashion side. Throughout my 40 years of visiting Indonesia to explore the indigenous weaving arts of the Batak people, I have become increasingly aware of this. Since the onset of the colonial era, church, state, education, media, and the global economy have all served to inculcate in the people the colonial perception of themselves as being ‘without’ fashion. There is awareness (how could there not be?) of themselves as having (been situated in) an inferior culture, an inferior clothing system, of being uncivilised and needing to be developed and modernised. It was at this juncture that I asked, during the discussion, “What [given this insight] is the role of the anthropologist here?” From the questions posed, I perceive that there was more concern about my advocacy as an anthropologist than the advocacy inscribed in the colonial past and implicit in the fashion system, including fashion advertising of all kinds. In response, I claim that my (indeed dubious) ‘right’ to tell people what to do and to represent them paternalistically was not at issue here. At issue was this larger complementary conceptual system and my conviction that we need to take collective ownership of it, to deal ethically with how we are complicit in perpetuating that damaging system. This is true for both sides of the great global divide that the system creates.

My years of going back and forth to Indonesia have impressed upon me the seemingly indomitable magnitude of the machinery of modernity. We have all seen cartoons of a forest being fed into the mouth of a grinder that spews out toilet paper at the other end, a metaphor for how our economy and lifestyles transform something of eternal and essential value into an ephemeral commodity. I perceive that there is an analogy to be drawn here with the workings of industrial fashion. My Long Read was an attempt to point out that industrial fashion has become a system for transforming vibrant, meaningful, locally sustainable indigenous fashion systems into disposable fashion devoid of meaning. My goal was to make the unseen and obscured connection between the two dots of industrial fashion and indigenous clothing systems visible. I called attention to how the conceptual system within which we live and operate has shaped what we see and do not see. It has focused our lenses ethnocentrically on the fashion side, to the exclusion of the non-fashion side, and left out what is going on between the two. Ultimately, though, my point is that on both sides of the fashion divide, most of us are blind to the overarching conceptual system and its destructiveness.

I own up to wanting to expand the latitude of self-determination on both sides of the divide. I wrote the Long Read as an activist who is engaged in doing what I can to facilitate the changes needed for a future not-as-usual, but one that can engender sustainability and well-being. I chose, as an activist, to participate in the admirable and influential State of Fashion because of this desire to facilitate change. This was also my motivation for writing the Long Read. This is my recourse as an anthropologist. I am under no illusions about my capacity to influence choices taken by villagers in Indonesia. What is indomitably at operation, influencing choices is, among other things, the more than trillion-dollar engine of industrial fashion, its depiction of modernity, and its way of operating throughout the world, influencing political, economic, cultural and lifestyle choices. Let us challenge ‘the right’ of that system to impose itself everywhere! My power to make real change in a village is less than that of a flea to guide an elephant. The significant ethical issue for this Whataboutery is not how I conduct my fieldwork, but the workings of the industrial fashion system. In this, you and I are equally complicit. And the role, then, of an anthropologist? My writings and the Whataboutery are my answer to that question. Here and in Indonesia, I approach the issue of fashion and clothing systems in the same way: by discussing the implications of the dichotomised system of fashion. Raising awareness. That is my recourse.

And so to the question that was posed about how I try to facilitate agency: I hope that it is becoming clear from the above that, for me, facilitating agency was my ultimate goal in participating in the Whataboutery. The occasion presented a much coveted opportunity to share my insight into the need to shake free of the conceptual yoke that has shaped the operations of industrial fashion and polarised the world of dress. Anything less than this kind of radical revision will entail ‘playing the game’ within the terms set out by the current fashion system. In the end -- even if the violence is somewhat ameliorated --playing by the terms set by this system will only reinforce and expand the reach of industrial fashion and its conceptual baggage. This will, in turn, most likely engender further dependence on that system. The same goes for making so-called sustainable and even regenerative fashion. If these efforts take only the biophysical world and ecological footprint into account they will ultimately fail to alter the system. The many layers of fashion’s violence towards people and their cultures (not just garment workers) must also be addressed and redressed, and this will require that both sides of the fashion divide come to grips with the bigger picture. A paradigmatic shift is needed.

Just as the rejection of industrial fashion in the North has implications for garment workers in the South, I perceive that discussions on the two sides of fashion’s apparent polarity are complementary and mutually referential. Both continue to be informed by fashion’s colonial definition. I have proposed that respectful sharing of perspectives and intentions can lay an important foundation for a decolonial future. It makes sense that any steps towards an altered future must involve both sides.

I am not aware of having either the ambition or the capacity to tell ‘their story’ – rather to do my bit to help create the space to hear ‘their story’ about what it means to be situated on the other side of the great fashion divide. (See my film, ‘Uli’s Voice from a Sacrifice Zone of Fashion’ as an example (https://youtu.be/qVLxga3TOsM). I used the Whataboutery stage to share insights emerging from my experience of both the fashion and the non-fashion worlds. I felt the need to tell about the deep injustices and violence of the fashion dichotomy, to point to the destruction that it has caused for those putatively without fashion. I aspire to helping the ‘fashion side’ perceive the cultural destruction enacted by the fashion system and facilitate repair, to allow diversity to flourish once again. On both sides of the divide.

References

Holthaus, Eric. 2020. "The Future Earth: A Radical Vision for What’s Possible in the Age of Warming," Harper Collins.

Meyer, Aditi, 2020. ‘intervention 02: origins - an introduction’

https://www.stateoffashion.org/en/intervention/intervention-2-origins/origins-introduction

Niessen, Sandra. 2020a. Fashion, its Sacrifice Zone, and Sustainability, Fashion Theory, 24:6,859-877, DOI: 10.1080/1362704X.2020.1800984

Niessen, Sandra, 2020b. ‘Regenerative Fashion, there can be no other.’ Longread, State of Fashion Whataboutery # 2. https://www.stateoffashion.org/en/intervention/intervention-1-introspection/long-read-titel/

Niessen, Sandra, 2020c. ‘State of Fashion Whataboutery Series, ‘This is an Intervention’ 01’

Niessen, Sandra, 2020d. ‘State of Fashion Whataboutery Series, “This is an Intervention”’

Whataboutery #1 2020 REWATCH

About State of Fashion

https://www.stateoffashion.org/nl/about/

Vazquez, Rolando, 2020. Vistas of Modernity – decolonial aesthesis and the end of the contemporary. Mondriaan Fund Essay 014. Amsterdam: Mondriaan Fund.

Watch my latest film

Image © Karen Spurgin and Kirsten Scott

Kirsten Scott

Borrowed Cloth: Barkcloth

How can our affiliation with nature consciously be addressed through fashion in a way that creates clothing that makes us feel healthier? Can a socially - as well as environmentally - sustainable approach to fashion design be developed that integrates the health benefits of forest products? My research explores ways to create garments from a tree-based textile that are not only carbon-negative but also have a positive effect upon human health and wellbeing. This research takes a holistic approach in order to investigate the full potential of Ugandan barkcloth, produced from the wild fig tree, for responsible luxury clothing.

Kirsten Scott is a designer and practice-led researcher, whose work explores the modernisation of craft traditions for sustainable, luxury fashion, and argues the importance of the hand made and of indigenous knowledge systems in a technology driven industry.

She has worked extensively in Uganda on fashion–related development projects, navigating ethical concerns, the legacies of colonialism and the realities of the fashion market. Her methodology as a designer and researcher has become increasingly holistic and multi-disciplinary, concerned with fashion’s potential in benign design. Her practice adopts a slow approach that stands in opposition to the orthodoxies of speed and growth.